Black History Month

Overview

|

The School Violence Prevention Demonstration Program presents educators with lesson plans that explore the use of nonviolence in history, paying particular attention to the civil rights movement and African American history.

|

Download Lesson 1 (PDF) Download Lesson 1 Materials (ZIP)

Download Lesson 2 (PDF) Download Lesson 2 Materials (ZIP)

Download Lesson 3 (PDF) Download Lesson 3 Materials (ZIP)

Download Lesson 4 (PDF) Download Lesson 4 Materials (ZIP)

Download Lesson 5 (PDF) Download Lesson 5 Materials (ZIP)

Download Lesson 6 (PDF) Download Lesson 6 Materials (ZIP)

Additional Resources

Janice Kelsey's Story In this interview, civil rights movement foot soldier, Janice Kelsey, describes her experience in The Children’s March of 1963.

Dr. King on the Selma March—A very brief, but powerful clip in which King prepares foot soldiers for the March on Selma. He tells them, “If you can’t accept blows without retaliating, don’t get in the line.”

An American Hero: The Story of Congressman John Lewis—A fifteen-minute video that tells the story of civil rights hero Congressman John Lewis. It highlights the use of nonviolence in sit-ins and at specific events, such as the Birmingham Church bombing and the March on Selma.

The History Channel: Woolworth Lunch Counter—An engaging six-minute segment on the Woolworth sit-ins in Greensboro, Tennessee.

Charles Moore: I Fight With My Camera-—A long, but worthwhile piece in which photojournalist Charles Moore tells the story of the civil rights movement as he witnessed it through the lens of his camera.

Bridge to Freedom—A local news team retraces the steps of those who marched for voting rights across the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma, Alabama, in 1965.

Podcasts

60-Second Civics

Celebrate Black History Month with 60-Second Civics, the Center for Civic Education's daily podcast series. Here is what you can expect:

Week 1:

How Have Civil Rights Movements Resulted in Fundamental Political and Social Change in the United States? (episodes adapted from We the People: The Citizen & the Constitution, Level 3, Lesson 35)

Week 2:

The Six Principles of Nonviolence

Week 3:

Nonviolence and the Civil Rights Movement

Week 4:

Civil Rights Leaders and Foot Soldiers

Click here to download each week's episodes. Or, subscribe to the podcast and have each day's episode downloaded to your computer.

Subscribe to the 60-Seconds Civics Podcast:

RSS:

![]() Download Lesson 1 (PDF)

Download Lesson 1 (PDF)

![]() Download Lesson 1 Materials (ZIP)

Download Lesson 1 Materials (ZIP)

Lesson 1: The Power of Nonviolence: The Children’s March

Sculpture of Children in Jail Commemorating 1963 Children's March

Teacher’s Guide

Lesson Overview

This lesson introduces students to the Children’s March, also commonly referred to as the Children’s Crusade, which took place in Birmingham, Alabama, in May 1963. Students will understand why children were involved in the march, how children were prepared for the march, and what made it a success. The lesson asks students to imagine themselves as someone involved in the march and consider their competing responsibilities, values, and interests.

A lesson adapted from Foundations of Democracy has been provided for teachers who do not currently use School Violence Prevention Demonstration Program (SVPDP) curricula. The lesson, titled “How Should One Choose among Competing Responsibilities, Values, and Interests?” was adapted from the Responsibility portion of the text, Unit 1, Lessons 1 and 2, and Unit 3, Lesson 6.

The lesson defines responsibilities, values, and interests and examines situations in which people must make a decision among competing responsibilities, values, and interests. It can be used by itself in any classroom and does not require prior knowledge of SVPDP materials. The lesson should be reviewed by the teacher prior to class. It can be taught prior to the lesson on the Children’s March, or information from the lesson and can be used as appropriate.

Correlations to SVPDP curricula are found at the end of this lesson plan.

Suggested Grade Level

Middle school (grades 6–8)

Estimated Time to Complete

Approximately 50 minutes

Lesson Objectives

After completing this lesson, students will be able to

- describe the Children’s March, its purpose, methods, and outcome;

- identify the responsibilities, values, and interests of those involved in the march;

- evaluate the decision to involve children in the march.

Materials Needed

- Student lesson: “How Should One Choose among Competing Responsibilities, Values, and Interests?”

- Teacher’s guide: “How Should One Choose among Competing Responsibilities, Values, and Interests?”

- Teacher resource: The Children’s Crusade of the Birmingham Civil Rights Campaign

- “Ballad of Birmingham,” by Dudley Randall, 1965

- The Children’s Crusade of the Birmingham Civil Rights Campaign (Handout 1)

- Video: Janice Kelsey’s Story - [Chapter 1] [Chapter 2]

- Note-Taking Guide: Janice Kelsey’s Story (Handout 2)

- Responsibilities, Values, and Interests Chart (Handout 3)

Before the Lesson

Review or teach “How Should One Choose among Competing Responsibilities, Values, and Interests?”

Lesson Procedure

1. Beginning the lesson. Read Dudley Randall’s “Ballad of Birmingham.” Use the poem to pique students’ interest in the events behind the poem. Ask students whether the poem leaves them wondering about anything described or alluded to in the poem. Ask them if they can connect the poem to anything they have heard or learned about in the past.

2. Reading about it. As a class, read the Children’s Crusade of the Birmingham Civil Rights Campaign (Handout 1). Ask students to make connections between Handout 1 and the poem, “Ballad of Birmingham.”

3. Video viewing. Introduce the video, Janice Kelsey’s Story, by telling students that Kelsey was a foot soldier in the Children’s Crusade. Have students watch and listen actively using the Note-Taking Guide: Janice Kelsey’s Story (Handout 2).

- Discuss students’ reactions to Kelsey’s story.

- Discuss the outcome of the Children’s Crusade and what made this strategy successful in Birmingham.

4. Group work. Have students work in small groups to identify the responsibilities, values, and interests of the people listed below. Use the Responsibilities, Values, and Interests Chart (Handout 3). Each group can select one of the bullet points below and present its findings to the class. As an alternative, each member of a group can pretend to be of one of the people listed below and act out their response with other members of their small group.

- A parent whose son or daughter wants to participate in the march

- A student who wants to participate in the march

- Martin Luther King Jr. and James Bevel, who organized the march

- A teacher whose students walked out of class to march

- A Birmingham store owner

Discuss students’ findings and the decision to involve children in the civil rights movement.

5. Concluding the lesson. Discuss with the class the ways in which children today make a difference in their communities.

Correlations to the SVPDP Curricula

Foundations of Democracy, middle school level

Authority: Unit 1, Lesson 3

Unit 2, Lessons 6 and 7

Privacy: Unit 4, Lesson 9

Responsibility : Unit 3, Lessons 6 and 7

Unit 4, Lesson 11

Justice: Unit 1, Lesson 1

Unit 2, Lesson 2

Unit 3, Lessons 6 and 7

Unit 4, Lessons 11 and 12

Foundations of Democracy, high school level

Authority: Unit 1, Lesson 2

Unit 3, Lessons 6 and 7

Privacy: Unit 4, Lesson 9

Responsibility: Unit 3, Lessons 6 and 7

Unit 4, Lesson 11

Justice: Unit 1, Lesson 1

Unit 2, Lesson 3

Unit 3, Lessons 6 and 7

Unit 4, Lessons 10 and 11

We the People: The Citizen & the Constitution, Level 2 (middle school)

Unit 1, concepts from Lesson 3

Unit 5, Lessons 23, 25, 26

Unit 6, Lessons 29 and 30

We the People: The Citizen & the Constitution, Level 3 (high school)

Unit 1, Lesson 2

Unit 5, Lesson 27

Unit 6, Lessons 33, 34, and 35

Project Citizen, Level 1 (middle school)

What Is Public Policy and Who Makes It?

Project Citizen, Level 2 (high school)

Chapter 1: Introduction to Project Citizen

Chapter 2: An Introduction to Public Policy

Chapter 4: Why Is Citizen Participation Important to Democracy?

| © 2014, Center for Civic Education. All rights reserved. Permission is granted to freely reproduce and use this lesson for nonprofit, classroom use only. Copyright must be acknowledged on all copies. |

![]() Download Lesson 2 (PDF)

Download Lesson 2 (PDF)

![]() Download Lesson 2 Materials (ZIP)

Download Lesson 2 Materials (ZIP)

Lesson 2: The Power of Nonviolence: What Is Nonviolence? What Does It Cost?

Sculpture of Rosa Parks Sitting on Bus Seat Labeled "WHITE"

Teacher’s Guide

Lesson Overview

This lesson uses primary sources and stories of participants in the civil rights movement to introduce students to the concept of nonviolence. Students will analyze the characteristics, costs, and benefits of nonviolence, realizing that it is an active, intentional, and effective way to achieve goals.

Correlations to School Violence Prevention Demonstration Program (SVPDP) curricula are found at the end of this lesson plan.

Suggested Grade Level

Middle and high school (grades 7–12)

Estimated Time to Complete

Approximately 60 minutes

Lesson Objectives

After completing this lesson, the students will be able to

- describe the characteristics of nonviolence;

- discuss the costs and benefits of using nonviolence.

Materials Needed

- Student Say-So (Handout 1)—two copies per student

- KWL Chart on Nonviolence (Handout 2)

- Poster paper and markers for the KWL chart and for recording students’ ideas during discussion

- Characteristics, Costs, and Benefits Chart (Handout 3)

- Printer-friendly versions of the following:

- “Heed Their Rising Voices,” New York Times, March 29, 1960

- “Rosa Parks,” by Rita Dove, The Time 100, June 14, 1999

- An excerpt from Walking with the Wind, by John Lewis

- “‘School’ Prepares Negroes for Mass Return to Buses,” December 15, 1956

- “Notes from a Nonviolent Training Session,” by Bruce Hartford, 1963

Lesson Procedure

1. Beginning the lesson. Begin the lesson by asking students to respond individually to the statements contained in the Student Say-So (Handout 1). Students respond to the statements with - Agree (A), Disagree (D), or Unsure (U). They should complete the same handout after the lesson and discuss if/how their ideas have changed.

2. KWL chart on nonviolence. Complete the KWL Chart on Nonviolence (Handout 2) with students to activate prior knowledge and engage students in the lesson. Use the K column to record what students already know, or think they know, about nonviolence. Use the W column to record what they want to know. At the end of the lesson, complete the L column with facts the students have learned. This will also be the point in the lesson at which you invite students to make any necessary corrections to the K column as a result of their new learning.

3. Reading about it. Divide students into small groups. Assign each group one of the sources listed below. Ask the students to become “experts” on the source by reading and taking notes. Tell the students that at the end of the allotted time, they will present a summary of their source to the class. This summary should include specific examples from their source that demonstrate the characteristics, costs, and benefits of nonviolence. Review these terms with your class, if necessary. The Characteristics, Costs, and Benefits Chart (Handout 3) can be used to help students take notes.

- Heed Their Rising Voices,” New York Times, March 29, 1960: https://www.archives.gov/

exhibits/documented-rights/ exhibit/section4/detail/heed- rising-voices.html - “Rosa Parks,” by Rita Dove, The Time 100, June 14, 1999: http://www.yachtingnet.com/

time/time100/heroes/profile/ parks01.html - An except from Walking with the Wind, by John Lewis: http://www.tolerance.org/

activity/commitment- nonviolence-leadership-john-l - “‘School’ Prepares Negroes for Mass Return to Buses,” December 15, 1956: http://www.montgomeryboycott.

com/article_561215_schools.htm - “Notes from a Nonviolent Training Session,” by Bruce Hartford, 1963: http://www.crmvet.org/info/

nv1.htm

4. Whole-class discussion. Use the quotation below to stimulate the class discussion:

“Why direct action? Why sit-ins, marches and so forth? Isn’t negotiation a better path?” You are quite right in calling for negotiation. Indeed, this is the very purpose of direct action. Nonviolent direct action seeks to create such a crisis and foster such a tension that a community which has constantly refused to negotiate is forced to confront the issue. It seeks so to dramatize the issue [so] that it can no longer be ignored. My citing the creation of tension as part of the work of the nonviolent-resister may sound rather shocking. But I must confess that I am not afraid of the word “tension.” I have earnestly opposed violent tension, but there is a type of constructive, nonviolent tension which is necessary for growth.

—Martin Luther King Jr., 1963

Questions to guide discussion:

- According to this quotation, what is the goal of nonviolence?

- Why is nonviolence effective in achieving this goal?

- What have you learned today that demonstrates King’s point? Give specific examples from your reading.

5. Concluding the lesson.

- Complete and correct the KWL Chart on Nonviolence (Handout 2).

- Give students a fresh copy of the Student Say-So (Handout 1). Discuss to see if their attitudes toward nonviolence have changed.

Supplemental Activity: Write a Letter

Remind students that Malcolm X, at one time, did not believe that nonviolence was the best way to gain rights for African Americans. In 1964, he wrote, “Concerning nonviolence: it is criminal to teach a man not to defend himself when he is the constant victim of brutal attacks.” Write a letter from Martin Luther King Jr. to Malcolm X persuading him that nonviolence is the best way to seek justice for African Americans. Include the characteristics of nonviolence, why it is effective, and other reasons why it should be used. Address concerns that Malcolm X might have had about using this method.

Correlations to the SVPDP Curricula

Foundations of Democracy, middle school level

Authority: Unit 1, Lessons 1 and 3

Unit 2, Lessons 6 and 7

Unit 3, Lesson 8

Privacy: Unit 1, Lessons 1, 2, and 3

Unit 4, Lessons 9, 10, 11, and 12

Responsibility: Unit 1, Lesson 2

Justice: Unit 1, Lesson 1

Unit 2, Lesson 2

Unit 3, Lessons 6 and 7

Unit 4, Lessons 11 and 12

Foundations of Democracy, high school level

Authority: Unit 1, Lessons 1 and 2

Unit 2, Lessons 6 and 7

Unit 3, Lesson 8

Privacy: Unit 1, Lessons 1, 2, and 3

Unit 4, Lessons 9 and 10

Responsibility: Unit 1, Lesson 3

Unit 3, Lessons 5 and 6

Justice: Unit 1, Lesson 1

Unit 2, Lesson 3

Unit 3, Lessons 6 and 7

Unit 4, Lessons 10 and 11

We the People: The Citizen & the Constitution, Level 2 (middle school)

Unit 1, concepts from Lesson 3

Unit 5, Lessons 23, 25, and 26

Unit 6, Lessons 29 and 30

We the People: The Citizen & the Constitution, Level 3 (high school)

Unit 1, Lesson 2

Unit 5, Lesson 27

Unit 6, Lessons 33, 34, and 35

Project Citizen, Level 1 (middle school)

What Is Public Policy and Who Makes It?

Project Citizen, Level 2 (high school)

Chapter 1: Introduction to Project Citizen

Chapter 2: An Introduction to Public Policy

Chapter 4: Why Is Citizen Participation Important to Democracy?

| © 2014, Center for Civic Education. All rights reserved. Permission is granted to freely reproduce and use this lesson for nonprofit, classroom use only. Copyright must be acknowledged on all copies. |

![]() Download Lesson 3 (PDF)

Download Lesson 3 (PDF)

![]() Download Lesson 3 Materials (ZIP)

Download Lesson 3 Materials (ZIP)

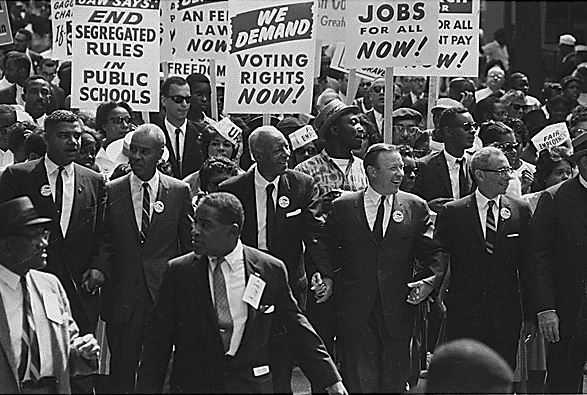

Lesson 3: The Power of Nonviolence: Change through Strategic Nonviolent Action

Nonviolent marchers demand "VOTES FOR WOMEN" on Fifth Avenue in New York City, 1912

Teacher’s Guide

Lesson Overview

Nonviolence is introduced to students as a concept with a deep history that reverberates in the present. The power of nonviolence as a catalyst for change is a function of both its philosophical foundations and the strategic application of specific nonviolent tactics. Students will analyze major figures in the history of nonviolence through the intellectual framework of what constitutes philosophical nonviolence as opposed to tactical nonviolence. The lesson guides students as they apply the analysis to a series of hypothetical situations that have been based on actual events. At the conclusion of the lesson, students should understand that nonviolence is both a philosophy and a strategy that has been and continues to be adopted by individuals and organizations to push for reforms.

Suggested Grade Level

Middle school and high schools (grades 7–12)

Estimated Time to Complete

Approximately 60 minutes

Lesson Objectives

After completing this lesson the students will be able to

- identify some of the major historical proponents of nonviolence;

- distinguish between the adherence to nonviolent philosophies (“philosophical nonviolence”) and the strategic application of nonviolent tactics (“tactical nonviolence”);

- describe various nonviolent tactics and the challenges that they present in their implementation;

- develop, present, and defend strategies aimed at bringing about change through nonviolence.

Materials Needed

1. Teacher Concept Paper: Nonviolent Resistance to Oppression

2. Five background information sheets on proponents of nonviolence

- Henry David Thoreau (Handout 1)

- Susan B. Anthony (Handout 2)

- Mohandas K. Gandhi (Handout 3)

- Martin Luther King Jr. (Handout 4)

- Cesar Chavez (Handout 5)

3. Copy for each student of Hypotheticals: Change through Strategic Nonviolent Action (Handout 6)

4. Articles on facts underlying hypothetical situations:

- Hypothetical 1: Based on Bob Jones University

- Hypothetical 2: Based on Shoal Creek Country Club

- Hypothetical 3: Based on John Pickle Co. in Tulsa, Oklahoma

- Hypothetical 4: Based on an article in USA TODAY

Lesson Procedure

1. Beginning the lesson. Ask students to share their understanding of nonviolence as a historical concept and as it practically applies to their everyday lives. Write the terms philosophy, tactics, and strategy on the board and have students free associate these with the concept of nonviolence. Write down the results of the free association on the board and leave it there for the duration of the lesson. Introduce the lesson topic and review the purpose of the lesson with students.

2. Studying historical proponents of nonviolence. Divide the class into pairs and distribute to each pair one background sheet on one of the following major proponents of nonviolence: Henry David Thoreau (Handout 1), Susan B. Anthony (Handout 2), Mohandas K. Gandhi (Handout 3), Martin Luther King Jr. (Handout 4), and Cesar Chavez (Handout 5). Each pair of students will focus on only one proponent. You might pause here to define proponent.

Ask each set of paired students to draw a table composed of three columns on a blank sheet of paper, with the columns labeled: (1) Who am I? (2) What did I believe? (3) How did I act on my beliefs? After reading the background information, the students should write notes in each column that respond to the question being posed about their assigned proponent.

After students have completed the columns, call on each pair to report highlights of their notes to the class. Use these to create a master table on the board for each of the proponents.

Please note that more than one pair of students can be assigned the same proponent. Teacher may then call on pairs who worked on the same proponent at the same time.

3. Defining philosophy v. tactics. Return to the free association between philosophy, tactics, strategy, and nonviolence. Ask the entire class to categorize the quotes and actions in the background sheets as reflecting either philosophical or tactical nonviolence. Guide the class as it comes up with working definitions of philosophical nonviolence and tactical nonviolence. What is the difference between the two? Are the two indivisible? Why does it matter whether something gets labeled as philosophical or tactical? Does a nonviolence strategy require both? Please note that useful background information for teachers may be found in the Teacher Concept Paper: Nonviolent Resistance to Oppression.

4. Tackling change hypotheticals. Distribute the hypothetical situation sheet to students, and then divide the class into four groups, assigning one of the four hypothetical situations to each group. Explain that each hypothetical situation sheet describes a situation that the students, as a group, will seek to reform. Ask students to work in their groups to develop a nonviolent strategy that reflects their own nonviolence philosophy (if any) and includes specific nonviolent tactics to bring about the desired reforms. The strategy and a clear statement of its objectives should be prepared for presentation to the class. Visual aids may be used to complement the presentation.

Ask each group to present its hypothetical situation and its proposed strategy of nonviolent action aimed at reform. The other groups should offer constructive critiques of the student group proposals following the presentation. Time permitting, presenting groups may respond to the critiques of their proposals.

5. Concluding the lesson. To conclude the lesson, distribute articles describing the factual situations that served as the basis for the hypotheticals. Lead students in a discussion comparing the hypothetical situations to the actual facts and examine the types of nonviolent tactics actually used and their effectiveness.

6. Assessment. Assign students to search for articles about a current situation that they would like to change. Ask the students to write one-page memos addressed to their fellow students summarizing the situation and then presenting a nonviolent campaign aimed at reforming the situation. In their memo, students may also predict the reaction to their proposed campaign and how best to anticipate and address that response.

| © 2014, Center for Civic Education. All rights reserved. Permission is granted to freely reproduce and use this lesson for nonprofit, classroom use only. Copyright must be acknowledged on all copies. |

![]() Download Lesson 4 (PDF)

Download Lesson 4 (PDF)

![]() Download Lesson 4 Materials (ZIP)

Download Lesson 4 Materials (ZIP)

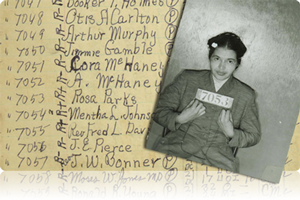

Teacher’s Guide

Lesson Overview

This lesson asks students to revisit the well-known story of a figure in the civil rights movement—Rosa Parks—through the primary source documents associated with her arrest in 1955. The arrest occurred in the shadow of the Supreme Court decision in Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka (1954) and had a powerful impact on the public policy of segregation and the application of the equal protection clause of the Fourteenth Amendment.

This lesson can be used to either introduce or enhance a unit on the equal protection clause of the Fourteenth Amendment or the civil rights movement. For teachers not currently using the School Violence Prevention Demonstration Program (SVPDP), the lesson can be used as is. For those who are using the SVPDP curriculum, this lesson allows students to apply the concepts of authority and issues of distributive, corrective, and procedural justice to a historical event. It also demonstrates the concepts taught in the We the People: the Citizen & the Constitution lessons on equal protection of the law. Specific references to individual lessons in the curriculum are found at the end of this guide.

Students will examine the documents at pre-designed stations and complete a journal (provided) using their observations. The class will then discuss findings and apply what they have learned about the Fourteenth Amendment, Jim Crow laws, and civil rights.

Suggested Grade Level

Elementary/Middle School (grades 5–8)

Estimated Time to Complete

Approximately 50–90 minutes

Lesson Objectives

After completing this lesson, students will be able to do the following:

- use primary source documents to make observations and take notes

- correct possible misconceptions about events on the day Rosa Parks was arrested

- apply what they have learned about the Fourteenth Amendment

- evaluate the actions of the three key players (Rosa Parks, the bus driver, and the arresting officer) on the day of Rosa Parks’s arrest, based on the standards set by the Municipal City Code of 1955 and the Fourteenth Amendment

Materials Needed

- Montgomery City Code (five to ten copies)

- Diagram of the bus (five to ten copies)

- Arrest Report, page 1 (five to ten copies)

- Arrest Report, page 2 (five to ten copies)

- Student Journal: The Arrest Records of Rosa Parks (one copy for each student)

- “Teaching with Documents: An Act of Courage, The Arrest Records of Rosa Parks”

(one copy for each student) - A copy of the Fourteenth Amendment

Before the Lesson

Review this guide and all materials provided.

Set up four stations around the room. At Station One, place several copies of the Montgomery City Code; at Station Two, place several copies of the diagram of the bus; at Station Three, place several copies of the first page of the police report; and at Station Four, place several copies of page two of the police report (students will likely need help deciphering the handwriting on this page). For large classes, set up two sets of four stations, or complete this lesson in the school library, where you may have more room to move around.

For SVPDP teachers: Read or review We the People: The Citizen & the Constitution, Level 1, Lesson 19, or Level 2, Lesson 26.

Lesson Procedure

1. Beginning the lesson. Ask students to share aloud everything they know about Rosa Parks. Write their answers on a chalkboard or chart paper. This should be done fairly quickly and conducted similar to a brainstorm activity, where there are no right or wrong answers. Simply list the responses, and then set them aside to return to later in the lesson.

2. Working with primary source documents. Tell students that they will examine the experience of Rosa Parks on the day she refused to give up her seat on a city bus to a white. Explain to students that they will be looking at copies of the actual papers pertaining to her arrest.

Help students differentiate between primary and secondary source documents.

Give each student a journal and ask them to go to each of the four stations to look at the documents and write about what they see, answering the questions provided. (They do not need to go to the stations in order. Students may disperse to view the documents individually, or you might choose to have them visit the various stations in assigned groups.)

3. Sharing their findings. After students have visited all four stations and returned to their seats with their journals completed, distribute copies of “Teaching with Documents: An Act of Courage, The Arrest Records of Rosa Parks.”

Read the first paragraph of “Teaching with Documents,” then have students look at their answers from Station One.

- What does Section 10 require bus drivers to do? (Answer: Keep the races separate on the bus.)

- What kind of authority does Section 11 of the Montgomery City Code give bus drivers? (Answer: The same authority as police officers.)

- How is the bus driver supposed to use his authority according to Section 11? (Answer: The bus driver is supposed to use his authority to keep the races separate.)

Read the second paragraph of “Teaching with Documents,” and direct students’ attention to the diagram of the bus. Show students the first ten seats that were designated as the white section of the bus. Point out that Rosa Parks was not in the white section of the bus.

Ask the following questions:

- Which rule in the Montgomery City Code that you just read support Rosa Parks’s position that she should not have to move? (Answer: She wasn’t in the white section; the races were still separate.)

- What language in the Montgomery City Code supports the bus driver’s position? (Answer: The bus driver has the authority of a police officer. It is unlawful for “any passenger to refuse or fail to take a seat among those assigned to the race he belongs.”)

Read the third paragraph of “Teaching with Documents.”

Remind students that Rosa Parks was charged with “refusing to obey orders of bus driver,” which was against the city code at the time. Remind them that there was a higher law, however: the Fourteenth Amendment of the U.S. Constitution, the highest law in the land. Ask students to review or apply what they have learned about the Fourteenth Amendment to this situation.

- How was Rosa Parks’s arrest seemingly a violation of the Fourteenth Amendment? Was there a good and fair reason for her not to sit anywhere she liked on the bus?

- Why were states able to have laws upholding segregation when the Constitution said that people were entitled to “equal protection under the law?”

- Rosa Parks’s mother asked her, “Did they beat you?” How does her question demonstrate that the Fourteenth Amendment was not being upheld in Montgomery, Alabama?

- From what you have learned from this account and others, does it seem like “separate” was ever “equal”? Give examples.

Read the fourth paragraph of “Teaching with Documents.” Emphasize to students that Mrs. Parks was very active in the local chapter of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). Tell them she is often portrayed as someone who was “just tired,” but in reality she was someone who had struggled against segregation for a long time.

Look at page one of the police report from Rosa Parks’s arrest.

- What did the bus driver say was the problem? (Answer: A black woman was sitting in the white section of the bus and would not move to the back.)

Ask: Is that a true statement? Was Rosa Parks seated in the white section of the bus? - Which city code was Rosa Parks charged with violating? (Answer: Section 11: Powers of persons in charge of vehicle; passengers to obey directions.)

- What date was this report written? (Answer: December 1, 1955)

Ask the following questions:

- Is it always wrong to disobey laws and rules?

- What are some consequences of disobeying laws and rules?

Explain that Rosa Parks and others in the civil rights movement disobeyed rules and laws and accepted the consequences as a way to demonstrate that the laws were unjust and wrong. By responding nonviolently to mistreatment, they were powerful in their efforts to bring about change.

Look at page two of the police report from Rosa Parks’s arrest.

- What does it list as the charges against Rosa Parks? (Answer: Refusing to obey orders of a bus driver.)

- What is listed as Rosa Parks’ nationality? (Answer: Negro)

- Nationality refers to the country in which one is born or of which one has become a citizen. Rosa Parks was born in America. Why do you think the police did not list her nationality as “American”? (Answers will vary.)

Ask the following questions:

- Does it seem from this report that African Americans in Montgomery were viewed as full-fledged American citizens? What would have been listed under “Nationality” if the police officer had viewed Rosa Parks as an American citizen?

- How might being considered noncitizens affect the way African Americans were treated by police officers and other officials?

- The Montgomery City Code says that equalbut separate accommodations must be provided for whites and “negroes.” Thinking about Rosa Parks’s experience, were equal accommodations provided?

- What is the danger in saying things are equal when they are not?

- What we have learned. Look back at the list the students developed at the beginning of the class, and ask them the following:

- How much of their list was accurate?

- What was inaccurate or perhaps a misconception?

- What have they learned about Rosa Parks or the events of that day?

- What is the value of working with primary source documents?

Help students understand how Rosa Parks’s arrest began the Montgomery Bus Boycott and led to Parks being known as the “mother of the modern civil rights movement.” Remind students that the ruling in Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka (1954) declared that separate but equal educational facilities are unconstitutional—the decision pertained only to schools—and that the Civil Rights Act of 1964 legally ended segregation in public places.

Correlations to SVPDP Curricula

Foundations of Democracy, Elementary School Level

Authority: Unit 1, Lessons 1 and 3

Unit 2, Lessons 7 and 9

Unit 4, Lesson 11

Justice: Unit 1, Lesson 1

Unit 2, Lessons 2 and 3

Unit 3, Lessons 5 and 6

Unit 4, Lessons 9 & 10

Responsibility: Unit 1, Lesson 1

Unit 2, Lessons 3 and 4

Unit 3, Lessons 6 and 7

Foundations of Democracy, Middle School Level

Authority: Unit 1, Lessons 1 and 3

Unit 3, Lesson 6

Unit 4, Lessons 8 and 9

Unit 5, Lessons 12 and 14

Responsibility: Unit 1 Lessons 1 and 2

Unit 2, Lesson 4

Unit 3, Lesson 5

Justice: Unit 1, Lesson 1

Unit 2, Lesson 3

Unit 3, Lessons 7 and 8

Unit 4, Lessons 10, 11, and 12

We the People: The Citizen & the Constitution

Level 1 (Elementary) Lesson 19

Level 2 (Middle School) Lesson 26

Project Citizen, Level 1

“What is Public Policy and Who Makes It?”

This lesson was developed under a grant from the U.S. Department of Education. However, the contents of this lesson do not necessarily represent the policy of the Department of Education, and you should not assume endorsement by the federal government.

©2012. Center for Civic Education. All rights reserved. Permission is granted to freely reproduce and use this lesson for nonprofit, classroom use only. Copyright must be acknowledged on all copies.

| © 2014, Center for Civic Education. All rights reserved. Permission is granted to freely reproduce and use this lesson for nonprofit, classroom use only. Copyright must be acknowledged on all copies. |

![]() Download Lesson 5 (PDF)

Download Lesson 5 (PDF)

![]() Download Lesson 5 Materials (ZIP)

Download Lesson 5 Materials (ZIP)

Lesson 5: The Power of Nonviolence: CITIZENSHIP SCHOOLS AND CIVIC EDUCATION

CITIZENSHIP SCHOOLS AND CIVIC EDUCATION

DURING THE CIVIL RIGHTS MOVEMENT AND IN THE PRESENT

Teachers Guide

Lesson Overview

This lesson is intended to help guide students through a historical and contemporary examination of citizenship schools and civic education. During the civil rights era, citizenship schools were an integral part of the effort to educate African Americans about the rights that they had as United States citizens so that they could vigorously assert these rights in the fight against segregation. Presently, citizenship education tends to be associated with efforts to prepare noncitizens to meet the requirements for becoming naturalized U.S. citizens. Underpinning both forms of citizenship education is the concept of civics or civic education, defined by John J. Patrick as the “development of intellectual skills and participatory skills, which enable citizens to think and act in behalf of their individual rights and their common good” in a constitutional democracy. [1]

For teachers not currently using the School Violence Prevention Demonstration Program (SVPDP), this lesson can be used as is. For those who are using the SVPDP curriculum, this lesson allows students to apply the Foundations of Democracy concepts of authority and responsibility. It also demonstrates concepts taught in We the People: The Citizen & the Constitution. Specific references to individual lessons in the curriculum are found at the end of this guide.

Suggested Grade Level

Middle school and high school

Estimated Time to Complete

45 minutes

Objectives

After completing this lesson, students will be able to

• explain the role that citizenship schools played during the civil rights movement, particularly in regard to preparing for state voting and literacy tests;

• identify at least two of the main objectives and instructional means of a citizenship school based on a study of the Highlander Folk School;

• compare the purpose of citizenship schools in the past with the objectives of citizenship schools in the present; and

• develop a list of three to five basic elements comprising a civic education, regardless of past or present.

Materials Needed

• Historical Information on Citizenship Schools

• 60-Second Civics: Septima Clark (http://www.civiced.org/index.php?page=audio&&mid=336)

• Excerpts of Interview with Septima Clark (http://docsouth.unc.edu/sohp/G-0017/excerpts/excerpt_2165.html; http://docsouth.unc.edu/sohp/G-0017/excerpts/excerpt_2167.html)

• 1965 Alabama Literacy Test

(www.ccle.fourh.umn.edu/literacy.pdf)

• U.S. Naturalization Test (www.history.com/images/media/pdf/100qENG.pdf)

Before the Lesson

Review this guide and all of the materials provided.

Lesson Procedure

1. Beginning the lesson. Ask each of your students to write a one-sentence definition of “citizenship.” As a class, discuss what the students came up with and list some of the important elements of the definition: which should include most or all of the following: rights, duties, citizen, member, society, disposition, conduct, and community. Follow up by posing an open question: What is a “citizenship school”?

2. Introducing Septima Clark and Citizenship Schools. Arrange for students to listen to the 60-Second Civics episode on Septima Clark, or use the transcript provided. Why was Septima Clark later called the “queen mother of the civil rights movement”?

Analyze how citizenship classes were conducted at Highlander Folk School and elsewhere during the civil rights era by listening to or reading the excerpts from an interview with Septima Clark and the historical background provided. Have students discuss what made this method of instruction both necessary and effective.

3. Analyzing documents. Read some of the questions in the 1965 Alabama literacy test, which was intended to discourage or prevent African Americans from voting. Ask the students to assess the difficulty of the questions. Are any of the questions tricky or unfair? How relevant were any of these questions to the act of voting? How might such questions have presented obstacles to qualifying for voter registration? How might the obstacles have been surmounted?

Gauge student familiarity with the requirements to become a “naturalized” citizen of the United States. Specifically, ask students to consider the naturalization test requirement and the preparations needed to pass this test. What are the similarities and distinctions between citizenship education as it pertains to passing something like the 1965 Alabama Literacy Test and the U.S. Naturalization Test?

Working in groups or as individuals, ask students to compare the 1965 Alabama Literacy Test with the current U.S. Naturalization Test. They should note that the first test had to be taken by a select group of people who were already citizens, while the second test must be taken by persons applying to become citizens. Are there any similarities or differences in the questions?

4. Where are we today? Ask students to consider the role of citizenship schools and civic education today. The following questions can help guide the discussion:

• How might citizenship schools be conducted today?

• What purpose would they serve?

• Are courses in “civics” beneficial only to persons who are applying for citizenship?

• Are you—as students—currently engaged in civic education?

• If so, is it anything like the forms of citizenship education that you have been examining?

Students should understand that, in the broad sense, citizenship schools and civic education both consist of educational programs that are designed to instruct students as to the rights and responsibilities of citizenship, while also imparting the knowledge and skills necessary to exercise those rights and responsibilities.

Additional Resources

• http://www.crmvet.org/info/lithome.htm

• http://www.crmvet.org/tim/timhis54.htm#1954ccs

• http://memory.loc.gov/ammem/aaohtml/exhibit/aopart9b.html

• “Lighting The Way: Nine Women Who Changed Modern America” by Karenna Gore Schiff, Miramax Books

• http://www.pbs.org/newshour/extra/teachers/lessonplans/us/july-dec08/constitution_day.html

Correlations to SVPDP Curriculum

Foundations of Democracy, Elementary School Level

• Authority

• Unit 1, Lessons 1 and 3

• Unit 2, Lessons 7 and 9

• Unit 4, Lesson 11

• Justice

• Unit 1, Lesson 1

• Unit 2, Lessons 2 and 3

• Unit 3, Lessons 5 and 6

• Unit 4, Lessons 9 and 10

• Responsibility

• Unit 1, Lesson 1

• Unit 2, Lessons 3 and 4

• Unit 3, Lessons 6 and 7

Foundations of Democracy, Middle School Level

• Authority

• Unit 1, Lessons 1 and 3

• Unit 3, Lesson 6

• Unit 4, Lessons 8 and 9

• Unit 5, Lessons 12 and 14

• Responsibility

• Unit 1 Lessons 1 and 2

• Unit 2, Lesson 4

• Unit 3, Lesson 5

• Justice

• Unit 1, Lesson 1

• Unit 2, Lesson 3

• Unit 3, Lessons 7 and 8

• Unit 4, Lessons 10, 11, and 12

• We the People: The Citizen & the Constitution

• Level 2 (Middle school), Lessons 26 and 29

• Level 3 (High school), Lessons 17 and 19

This lesson was developed under a grant from the U.S. Department of Education. However, the contents do of this lesson do not necessarily represent the policy of the Department of Education, and you should not assume endorsement by the federal government.

© 2011, Center for Civic Education. All rights reserved. Permission is granted to freely reproduce and use this lesson for nonprofit, classroom use only. Copyright must be acknowledged on all copies.

[1] Patrick, John J. "Civic Education for Constitutional Democracy: An International Perspective. ERIC Digest." ERICDigests.Org - Providing Full-text Access to ERIC Digests. ERIC Clearinghouse for Social Studies/Social Science Education Bloomington IN., 00 Dec. 1995. Web. 15 Feb. 2011. <http://www.ericdigests.org/1996-3/civic.htm>.

| © 2014, Center for Civic Education. All rights reserved. Permission is granted to freely reproduce and use this lesson for nonprofit, classroom use only. Copyright must be acknowledged on all copies. |

![]() Download Lesson6 (PDF)

Download Lesson6 (PDF)

![]() Download Lesson 6 Materials (ZIP)

Download Lesson 6 Materials (ZIP)

Lesson 6: The Power of Nonviolence: Music Can Change the World

The Power of Nonviolence: Music Can Change the World

Lesson Overview

Students explore how music can be used to attain social and political changes in society. The lesson continues the theme of nonviolence by exploring ways in which music helped advance the civil rights movement.

Suggested Grade Level

Middle school and high school

Estimated Time to Complete

Up to two class periods

Objectives

After completing this lesson, students will be able to

• discuss how music can positively influence social and political issues in society,

• identify how specific pieces of music have had an impact on the civil rights movement, and

• explain the motivation or inspiration of various composers for becoming involved musically.

Materials Needed

• A laptop, speakers, and internet connectivity or a tape recorder with preselected songs

• Lyrics and fact sheet for "We Shall Overcome" (Handout 1)

• Song list (Teacher Resource 1)

• Student direction sheet (Handout 2)

Before the Lesson

• Determine how the various musical selections will be shared with the class and with the groups.

• Decide how long the groups will have to gather information and then prepare for a short presentation to the class.

• Determine how long each group's presentation will be.

Lesson Procedure

Day 1

1. Beginning the lesson. Using the blackboard or a screen, share the following quote from Berthold Auerbach: “Music washes away from the soul the dust of everyday life.” Begin a class discussion by asking students what they think of this quote. Ask students to share the following:

• What do they think of music?

• What kind of music do they listen to and why?

• How often do they listen to music, and how accessible is it today?

• Provide current and historic examples of negative influences attributed to music.

• Provide current and historic examples of positive influences attributed to music.

To help transition from this discussion to the next segment, share one or more of the following quotes and ask students to discuss their meaning. Also solicit any examples the students can recall.

"Music can change the world because it can change people." —Bono

"Music doesn't lie. If there is something to be changed in this world, then it can only happen through music." —Jimmy Hendrix

“One good thing about music, when it hits you, you feel no pain.” —Bob Marley

2. Music as an instrument of social change. Play a modern-day popular protest song, such as Macklemore and Ryan Lewis’s “Same Love.” Lyrics can be found at http://www.azlyrics.com/lyrics/macklemore/samelove.html. Engage your students in a class discussion:

• Ask students to discuss the meaning of the modern-day protest song you have chosen and to explain why it has become popular.

• What other social issues have been discussed through music? Name the issues and the songs.

• How has music helped to bring about social or political change? Give examples.

• Can you think of songs associated with the civil rights movement of the 1950s and 1960s?

3. A civil rights song—"We Shall Overcome." Play this song for the students and ask them to identify the song and its meaning. Below are two options. Many other renditions of this song are available online. The lyrics and a fact sheet for the song are provided in Handout 1. Discuss with students the origins of this song from gospel music and old spiritual songs. What other eras can they associate with spirituals?

• Sung by Pete Seeger: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2b24Ewk934g

• Sung by various artists: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jW2MRTqzJug

4. A songwriter and his or her song. This group activity will allow students to research some of the most compelling pieces of music and the stories behind them. Divide the class into groups of four. Give each group one of the songs on the song list (Teacher Resource 1). Students will first need to read the lyrics and, if possible, listen to the song. Ask students to complete the following activity:

• Determine whether the song speaks specifically about a real-life event or incident, and compare what the song describes with the actual event, or whether the song is a general commentary on the state of affairs at the time. If so, what aspects of social injustice does the song describe?

• Who was the singer/songwriter of the piece? What was his or her connection to the civil rights movement?

• What impact, if any, does a song like this have on the social consciousness of a community or society? Please distribute the student direction sheet (Handout 2) provided. This should be the stopping point for the first class. Tell students how long the groups have to complete the research and compile the responses for the activity.

Day 2

5. Reconvening the group. Divide the class into the groups formed for the activity. Give them a few minutes to prepare themselves for sharing their work.

6. Sharing. Ask each group to share with the rest of the class their chosen or assigned song and their responses to the questions. Have the songs on hand in the event that the other students have not heard the song before. You may wish to have them listen to at least one or two songs, depending on how much time you have.

7. Concluding the lesson. Once all the groups have shared, ask the students to reflect on what they have heard and conduct a class discussion. Some questions that can be used are as follows:

• What have you learned from this exploration?

• The music in this activity spanned almost thirty years. Why did it take so long to have an impact?

• What role did the songwriters and singers play in this movement?

• Could music have the same impact today? Why or why not?

| © 2014, Center for Civic Education. All rights reserved. Permission is granted to freely reproduce and use this lesson for nonprofit, classroom use only. Copyright must be acknowledged on all copies. |